Editor’s Note: This is part of a series of posts describing the construction of a net-zero energy house in Rochester, Minnesota, by Tracee Vetting Wolf, Matt Vetting, and their son Max. You can find their complete blog here. A list of their previous posts appears at the bottom of this column. This post was written by Tracee.

Air conditioning was invented in 1902 to solve a printing press problem at Sackett and Wilhelms Lithography & Printing Company; it helped dry the ink in a way that didn’t mess up the alignment and warp the paper. During particularly hot weather, the printing area became a popular place to find relief during the lunch hour and Willis Carrier, the inventor, realized its potential for human comfort.

He took it to movie theaters where the public was exposed to it for the first time. An interesting fact: The first air conditioning installed in a private home was in 1914 in Minneapolis. By the 1960s, what was once a luxury and a status symbol for the wealthy, was becoming affordable and widespread. By 1980 55% of houses in the U.S. had air conditioning and today it’s close to 90%.

As air conditioning became pervasive, there was less need for architecture that was designed to heat and cool passively. Architecture that is designed to local conditions, constraints, and resources is called vernacular architecture. With air conditioning, the tricks-of-the-trade for passive cooling designs were no longer essential to comfort. Houses could take a more arbitrary or mass-produced approach. It has changed the aesthetics of our architectural forms and created dependency on AC and energy consumption. In terms of human comfort, it has created a thermally constant state that removes the joy of thermal variation. And, I would argue, AC has caused us to lose a precious place-making attribute; we can no longer recognize the authentic sensibilities of a place by the design of its buildings.

To hear this fascinating story, listen to this 99% Invisible podcast.

Sustainability and the renewal of vernacular appreciation

It would be tough to wean ourselves from our AC addiction mostly because our buildings become uninhabitable without it. But faced with our energy consumption and greenhouse emissions from AC, we can’t, not think about it.

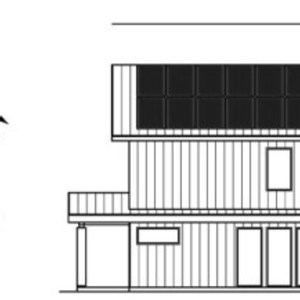

Matt and I became interested in passive house design principles because we didn’t want to have a utility bill anymore. And we knew that designs that are empathetic to the climate are empathetic to comfort. As a trained architect, I am also deeply appreciative of the place-making attributes of vernacular architecture. Here is the inspiration image we used at the start of our design process for the exterior of our home:

This is the inspiration image we used for the interior of our home:

We love the exterior for the sense of place the form and details allude to. We love the interior for the light and simplicity. And importantly, these inspiration sources carry with them a sense of identity and heritage; my ancestors came from Malmo and settled in northern Minnesota. The Nordic sensibility of the Midwest isn’t just about frigid and sparkly white winters, its people knew how to live well in this climate.

You can probably recognize some passive house strategies in these pictures, but the strategies we chose to employ for our house bear mentioning explicitly:

- Generous south-facing windows (with minimal windows elsewhere).

- Thermal mass to collect passive heat in cold weather months (concrete floor on the main level).

- Adequate shading to block heat in summer months.

- Continuous insulation; double-stud wall construction ensures no thermal bridging.

- Super insulation (double-stud wall construction to achieve nearly R-40).

- High-performance windows (we chose locally-made, triple-paned Wasco windows and doors).

- An energy recovery ventilator (ERV) to exchange heat from outgoing air to incoming air.

The overall mantra of passive house design is “maximize your gains, minimize your losses,” which provides the best path to net zero. Working with our builder to create a building envelope that is airtight (air infiltration rate less that 1 ach50), and the addition of extensive solar panels will complete our overall building performance aspirations.

So, when you’re driving south just past Rochester on Highway 52, and you see a red Swedish-looking house on the crest of a hill, perhaps you’ll recognize that you’re in Minnesota and get that hygge feeling in your heart.

Other posts about the Minnesota Homestead:

Why We Built an Energy-Efficient Home

Energy Planning for a Net-Zero Home

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

0 Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in